A Grand Design

New York City and its railroads weren’t shy. They were eager to proclaim their magnificence with a splendid monument—a fitting gateway to the nation’s exuberant financial, commercial, and cultural capital.

Yet Grand Central Terminal was more than just a pretty façade. Behind its lofty arches and elegant marble is a marvel of practical design and innovative engineering. The station not only looked like no other, it functioned like no other, merging elegance with efficiency.

Who Needs a New Station?

Though splendid in its day, the original Grand Central Depot of 1871 had become a 19th century relic struggling to meet the demands of a 20th century city.

Its 30-year-old rail tunnels couldn’t handle the steadily increasing traffic. The building lacked modern conveniences and signaling technology, as well as the infrastructure for electric rail lines. And having been designed for three independent railroad companies—with three separate waiting rooms—the terminal was badly outdated, crowded, and inefficient.

On top of that, the old station no longer reflected its surroundings. In 1870, 42nd Street was still a relative backwater. By 1910, it was the vibrant heart of a dynamic, ambitious, and swiftly growing New York City.

The Electrical Connection

Ash. Soot. Smoke. Steam-powered locomotives were dirty and detested. New York banned them south of 42nd Street in 1854. But they continued operating uptown.

Then, in 1902, two passenger trains collided in the smoke-clogged Park Avenue Tunnel. The state responded by banning steam locomotives within city limits, leaving the railroad in a pickle.

The solution? Electricity. But that meant redesigning the station for the new technology.

The Winner Is…

How to find an architect? Design competitions for major projects were commonplace in the early 1900s, and the railroad launched one in 1903. Four firms entered: McKim Mead & White; Samuel Huckel, Jr.; Reed & Stem; and Daniel Burnham.

Reed & Stem won. Its innovative scheme featured pedestrian ramps inside, and a ramp-like roadway outside that wrapped around the building to connect the northern and southern halves of Park Avenue.

But were these innovations enough to make Grand Central truly grand? The railroad wasn’t sure. So it hired another architect, Warren & Wetmore, which proposed a monumental façade of three triumphal arches.

The two chosen firms collaborated as “Associated Architects.” It was a stormy partnership, but the final design, combined the best ideas of both.

A Delight for the Eye

One of the splendors of Grand Central is that its vast, majestic spaces reveal extraordinary attention to the smallest design detail.

The architects brought in Parisian artist Sylvain Saliéres to craft bronze and stone carvings, including ornamental inscriptions, decorative flourishes, and sculpted oak leaves and acorns (symbols of the Vanderbilt family), including playful carved acorns festooning the Main Waiting Room’s chandeliers.

The architects specified Tennessee marble for the floors, Botticino marble for wall trim, and imitation Caen stone for the walls. The Oyster Bar’s vaulted ceilings are adorned with a herringbone pattern of Guastavino tiles—like those uptown in the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. On the exterior, imposing sculptures of Mercury, Hercules, and Minerva top the 42nd Street façade.

Elegance and Efficiency

Looks aren’t everything. New York City’s gateway had to be beautiful, majestic, and functional. The station had to impress people with its scale and style, yet also move travelers and trains swiftly and smoothly.

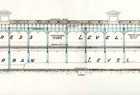

Behind Grand Central’s decorative flourishes are ingenious solutions. Looping tracks let arriving trains drop off passengers, continue ahead to pick up new passengers, and depart without having to turn around. Layered levels of train and subway lines pack enormous capacity into a relatively small footprint.

No detail was overlooked. When designing the indoor walkway ramps, engineers built mock-ups at various slopes and, according to The New-York Tribune, studied “the gait and gasping limit of lean men…fat men…women with babies…and all other types of travelers” to determine the ideal slope.